William Hogarth

Hamline University Permanent Art Collection

INTRODUCTION

In 2002 Hamline University acquired this portfolio of twenty-one Hogarth prints through the generous donation of Dr. George Vane, Professor of English at Hamline University from 1948-1988.

This exhibition is curated by Dr. Aida Audeh, Professor of Art History at Hamline University. Additional research on the history of engraving was done by Hamline University Studio Arts and English major Melanie Dowding ‘22.

Brief Biography of William Hogarth (1697-1764)

The English painter, engraver, and satirist William Hogarth was born in London, where he lived and worked all his life. When he was 10 his family was put in a debtors prison, and this experience provided William with a chance to develop the keen observation of human foibles that he was later to use in his art. At 16 he was apprenticed to a silversmith, and learned to engrave armorial designs on gold and silver work. But his frustrated artistic ambition led him to take up unorthodox methods of self-instruction, which ultimately contributed much to his originality as an artist. He set up in business as an engraver in 1720 and in the following year he produced his first dated engraving, a satire on the government's “South Sea Company” investment crisis.

In his “conversation pieces” Hogarth developed tentatively as a painter; but after joining the Free Academy of Sir James Thornhill (whose daughter Jane he married in 1729) he began to evolve a type of subject painting entirely new to English art, which the novelist Henry Fielding described as “comic-history”. These concerns are already apparent in Hogarth's first major work, a series of 12 plates based on Samuel Butler's Hudibras.

His first public success was the launching of a subscription for engravings of The Harlot's Progress paintings. Instead of issuing them through a printseller he published them himself, and reaped a handsome profit. In 1735 the engravings of A Rake's Progress (Sir John Soane's Museum, London) appeared; and in 1736 he painted two large religious scenes—inspired by his father-in-law's work—for St Bartholomew's Hospital.

At the time Hogarth was also illustrating Shakespeare, and deriving inspiration from the theater. In his portraits—such as that of his friend Thomas Coram (1740; Foundling Hospital, London), founder of the Foundling Hospital—Hogarth also attempted to compete with his Continental rivals. No further satirical prints were issued until 1745 when the Marriage à la Mode paintings (National Gallery, London) were engraved; the pictures themselves remained unsold until 1750/1.

In the later 1740s Hogarth's reputation began to wane, and he turned to producing prints from drawings rather than paintings. The subject matter of his prints became more popular (for example Gin Lane, Stages of Cruelty, 1751), and the organization of his paintings much simpler, as in The Wedding Banquet (c. 1745; County Museum and Art Gallery, Truro), possibly painted as part of a projected series concerning a “happy marriage”, where incident is reduced to a minimum and the paint takes on a purely expressive function.

In 1753 Hogarth published The Analysis of Beauty, the first formalist English art treatise, in which he related his experiments in form to their expression and meaning. Hogarth had done much to further the cause of English art, opening an art academy and urging the passing of an act to protect engravers from piracy, but his essentially anti-academic attitude made him unpopular in later life. In the 1750s the feeling of disillusionment in English politics brought on by the Seven Years War was reflected by a falling off in Hogarth's productivity, and his last years were marked by ill health and political quarrels.

Source: A Biographical Dictionary of Artists. Lawrence Gowing, ed. Windmill Books, 1995.

The Satirical Print in Eighteenth-Century England

Graphic satire was a branch of art with its own pictorial and textual traditions and conventions, with its own, highly distinct cultural identity and with its own attractions for the contemporary viewer and consumer. Like many other kinds of printed image, the graphic satire was also highly visible. Distributed to overflowing print shops and boisterous coffee houses, pinned up in cluttered street windows, scattered across crowded ship counters and coffee tables, and then passed from hand to hand, or hung and framed in glass, or pasted in folios bulging with other graphic images – the satiric print was a dynamic and mobile component of English graphic art, and a ubiquitous feature of contemporary urban life. In particular, graphic satire was associated with London – with the scores of engravers and print publishers who lived and worked in the centre of the great city; with the hundreds and thousands of Londoners who formed the primary audience for satiric prints; and with the anxieties and preoccupations, both political and social, that characterized the English capital in the early eighteenth century.

Source: Mark Hallett. The Spectacle of Difference: Graphic Satire in the Age of Hogarth. New Haven:Yale University Press, 1999.

A Brief History of Engraving

Engraving is a technique that has been used since as early as the fourteenth century, used for taking impressions on paper, likely as artist signatures. The action of engraving is the removal of material from a metal plate, traditionally copper, using a burin. The burin is a v-shaped, sharp, metal tool that is pushed into and along the metal plate to create these lines of removed metal in a piece. The removed lines are what will become the inked lines of a final print.

The technique originates from Germany, most prominently used by the Master of Playing Cards, an engraver who chiefly influenced the technique alongside the Master of the Year 1446. Many engravers in Germany took on these Master titles and reigned over specific themes of work. Engraving began to grow in Italy and Northern Europe, both areas following different paths of development in the art. By the late 15th century in Italy, engraving was primarily used to reproduce paintings, while in Northern Europe, it was used to create original works by engravers like Lucas van Leyden and Jan Gossaert.

In the 16th century, engraving began to flourish in unique possibilities, while simultaneously being restricted back to reproductions of paintings. More techniques were discovered for producing various tones, which would fluctuate in popularity over time. One technique called mezzotint almost entirely replaced engraving in the 18th century, until more modern artists have revived the technique, like Mauricio Lasansky and Stanley William Hayter, who use the technique for more abstract pieces and concepts.

In the mid-18th century, many engravers like Hogarth were producing works that other artists intended to copy. Many artists set out to copy Hogarth’s A Harlot’s Progress after its rise in popularity, which prompted Hogarth to take protective action over his work. Hogarth and other engravers actively expressed their disdain for plagiarism which directly led to the Engravers’ Copyright Act of 1735, often called Hogarth’s Act. Modern critics think of the copies as inferior to the original Hogarth engravings.

Written by: Melanie Dowding, Gallery Assistant (‘22)

Sources: Faramerz Dabhoiwala. The Appropriation of Hogarth's Progresses. Huntington Library Quarterly, 2012

Arthur M. Hind. A History of Engraving & Etching. New York: Dover Publications, 1923

Ad Stijnman. Engraving and Etching 1400-2000: A History of the Development of Manual Intaglio Printmaking Processes. Houten: HES & DE GRAAF, 2012

Prints from the Harlot’s Progress Series (1731-32)

Hogarth’s set of six images delineated the fluctuating fortunes of Moll Hackabout, a fictional character, from her first arrival in London as a naïve countrywoman to a death hastened by neglect, disease and medical incompetence.

The first plate of the series depicts the moment just after Moll has alighted from the York coach, when she is already on the point of being sucked into the city’s sexual subculture: Mother Needham, a notorious real-life procuress, reaches out a dubiously welcoming hand, while Lord Francis Charteris, an infamous rake and rapist, stares from a doorway.

In the second plate, Moll is shown in an expensively appointed apartment, having ascended the hierarchy of the prostitute’s profession to become the kept mistress of a wealthy man. In this image, she distracts her keeper, who is clearly paying a surprise visit, while her secret lover, only partially dressed after an interrupted assignation with Moll, escapes out of the door.

In the third plate, Moll is shown having returned to the seedier environs of Drury Lane, being waited upon by a ragged maid, and not realizing that she is about to be captured by the contemporary scourge of London prostitutes, Justice John Gonson, shown entering at the door.

Hamline University owns three of the six total prints of this series:

#577 A Harlot's Progress Plate I

#530 A Harlot's Progress Plate II

#529 A Harlot's Progress Plate III

Source: Mark Hallett. The Spectacle of Difference: Graphic Satire in the Age of Hogarth. New Haven:Yale University Press, 1999.

Prints from the Four Times of the Day Series (1738)

The sequential format of this series has antecedents in European pictorial traditions and as a series relates to A Harlot’s Progress and A Rake’s Progress. However, what unites each scene to the other is not the individual characters, none of which are repeated, but the passage of time itself. Hogarth seems to accentuate the notion of the ’progress of the day’, as well as that of an urban tour, by showing prominent figures walking across the compositions.

Night. The scene is set in a narrow street in Charing Cross, Westminster. The street is occupied by two taverns: the Earl of Cardigan on the left and the Rummer Tavern on the right. Both had functioned as Freemason Lodges in the 1730s. The foreground of Night is dominated by the figure of a drunken Freemason in full regalia being helped home. One might therefore interpret the scene of chaos in the foreground, dominated by the bonfire overturning a coach, as a humorous allusion to popular protest and unrest erupting into violent disorder and to contemporary conspiracy theories surrounding Freemasonry. Appropriately, as a member of a ‘secret’ society, the Freemason is seen walking under the cover of night.

Hamline University owns one print of four total of this series:

#539 Night

Source: Mark Hallett and Christine Riding. Hogarth. London:Tate Publishing, 2006.

Prints from the Marriage à la Mode Series (1745)

For centuries, the English have been fascinated by the sexual exploits and squalid greed of the aristocracy, and these are the subjects of one of the supreme achievements of British painting and engraving – Hogarth’s six-part series Marriage à la Mode, which illustrates the disastrous consequences of marrying for money rather than love.

The basic story is of a marriage arranged by two self-seeking fathers – a spendthrift nobleman who needs cash and a wealthy City of London merchant who wants to buy into the aristocracy. The title, though little else, is taken from John Dryden’s play of the same name first performed in 1672. Hogarth was a devoted play-goer and made his name as a painter with a scene from John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera. But for this series he invented the characters, plot and the title of each scene. The pictures were painted to be engraved and then offered for sale ‘to the Highest Bidder’ after the engravings were finished.

Marriage à la Mode was Hogarth’s first moralizing series satirizing the upper classes, which exposed the shallowness and stupidity of people with more money than taste who are unable to distinguish good from bad. The engravings were instantly popular and gave Hogarth’s work a wide audience. Like A Harlot’s Progress, they were offered to subscribers at a guinea a set. As a receipt for payment of the first half-guinea, subscribers were issued with a print of Hogarth’s etching Characters and Caricaturas, based on one of the sixteenth-century Italian artist Agostino Carracci’s sheets of caricatures. Hogarth intended to demonstrate that an infinite variety of characters could be shown without resorting to caricature.

Hogarth probably worked on the paintings of Marriage à la Mode throughout 1743, and perhaps in the early part of 1744. He had engraved his earlier series A Harlot’s Progress and A Rake’s Progress himself, but he decided to employ three French engravers who were working in London for Marriage à-la-Mode, each working on two plates in the series. The engravings, published in 1745, are uncolored, reversed versions of the paintings.

Plate I: The Marriage Settlement: The Earl of Squander is arranging the marriage of his son to the daughter of a rich Alderman of the City of London. The Alderman, who is plainly dressed, holds the marriage contract, while his daughter behind him listens to a young lawyer, Silvertongue. The Earl’s son, the Viscount, admires his face in a mirror. Two dogs, chained together in the bottom left corner, perhaps symbolize the marriage.

Plate II: The Tête à Tête: The young couple’s home reflects their own antipathy and disharmony. The tired Viscountess, who appears to have given a card party the previous evening, is at breakfast in the couple’s expensive house, which is now in disorder. The Viscount returns exhausted from a night spent away from home, probably at a brothel: the dog sniffs a lady’s cap in his pocket.

Plate III: The Inspection: The third scene takes place in the room of a French doctor (M. de la Pillule). The Viscount is seated with his child mistress beside him, he has apparently given her the venereal disease syphilis, as indicated by the black spot on his neck.

Plate IV: The Toilette: After the death of the old Earl the wife is now the Countess, with a coronet above her bed and over the dressing table, where she sits. She is talking to her admirer Silvertongue while having her hair dressed. She has also become a mother, and a child’s teething coral hangs from her chair. The lawyer Silvertongue invites her to a masquerade, like the one depicted on the screen to which he points.

Plate V: The Bagnio: This episode takes place in a bagnio. The word was traditionally used to describe coffee houses which offered Turkish baths, but by 1740 it meant a place where rooms were provided for the night with no questions asked. The Countess and the lawyer have retired there after the masquerade. The young Earl has followed them and is dying from a wound inflicted by Silvertongue, who escapes through the window, while the Countess pleads forgiveness.

Plate VI: The Lady’s Death: The final scene takes place in the house of the Countess’s father. She has taken poison on learning that her lover has been hanged for the murder of the Earl, reported in the broadsheet at her feet. Her child, deformed and crippled by congenital syphilis, embraces her and her father takes a ring from her finger. An apothecary scolds the servant whom he accuses of obtaining the poison.

Hamline University owns all six prints of this series:

#533 Marriage à la Mode Plate I

#532 Marriage à la Mode Plate II

#527 Marriage à la Mode Plate III

#526 Marriage à la Mode Plate IV

#525 Marriage à la Mode Plate V

#531 Marriage à la Mode Plate VI

Source: The National Gallery, London, UK entry on the paintings upon which the print series is based: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/william-hogarth-marriage-a-la-mode-1-the-marriage-settlement

Prints from the Industry and Idleness Series (1747)

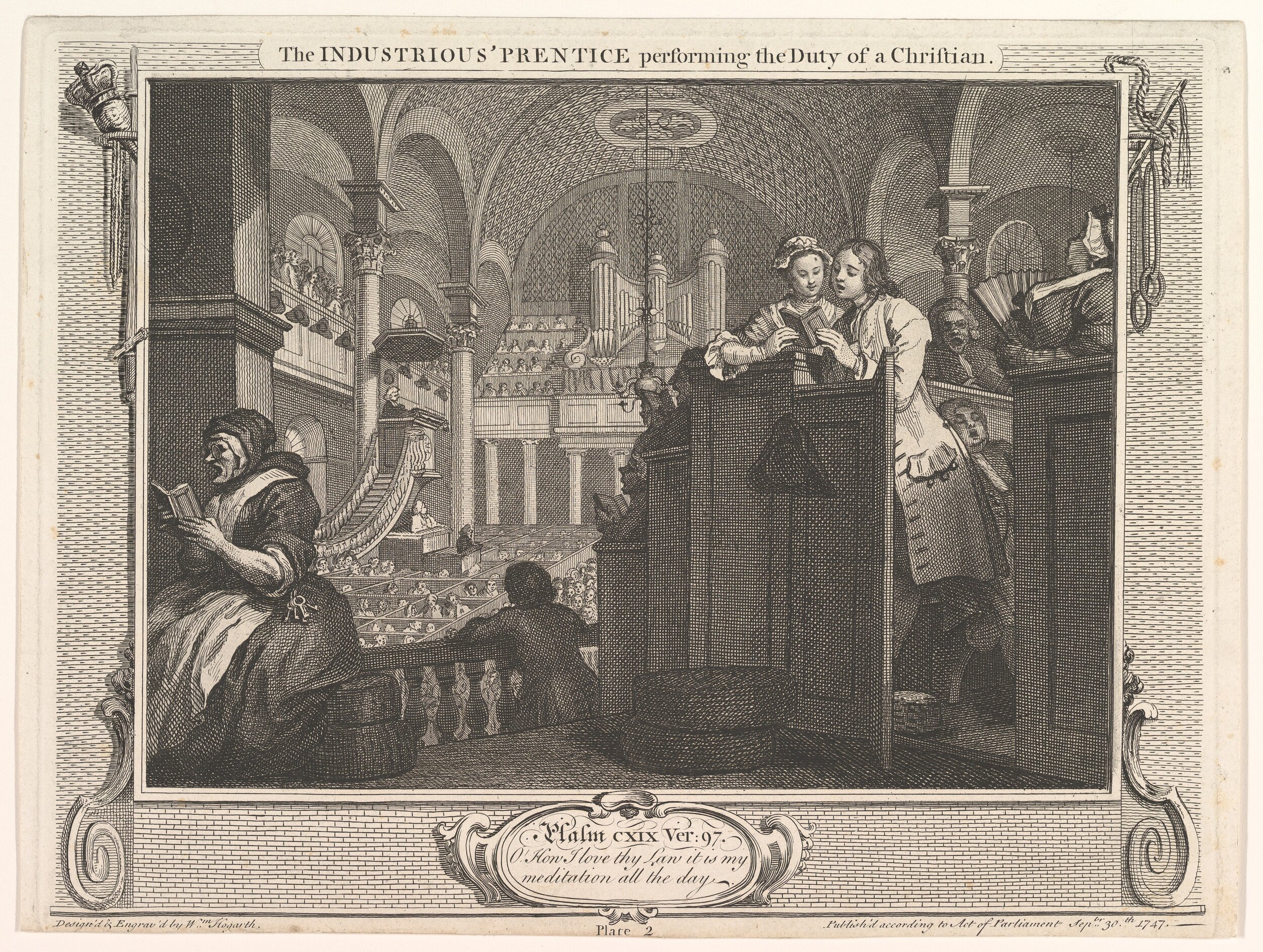

Comprising twelve individual images, this is the largest of Hogarth’s completed series. Although it deals specifically with the careers of two City apprentices and was ‘calculated for the use & Instruction of Youth’, the inclusion of biblical proverbs and quotations in cartouches at the bottom of each plate lend a religious context and universal significance to the work, as if Industry and Idleness constituted a modern-day Christian parable. Unusually in Hogarth’s work, the sequence shows the rewards of diligence and decency as well as the consequences of fecklessness and criminality. These are represented throughout by the trophies positioned to the upper left and right of each scene, the rewards of virtue symbolized by the chain, sword and mace of civic office and those of vice represented by irons (prison detention), a whip (corporal punishment) and the hanging rope (capital punishment).

The ‘good’ apprentice, Francis Goodchild, and ‘bad’ apprentice, Tom Idle, are seen together in Plates 1 and 10. Throughout the rest of the series their respective ‘careers’ are compared and contrasted. Goodchild’s expressions are serene and polite, his attire is orderly and his demeanor ever more elegant and gentlemanly, while Idle’s features become increasingly contorted and grotesque, and his posture slovenly and misshapen. The theme of order and disorder presented by the figures of Goodchild and Idle is mirrored by their respective environments. Initially, they share the same workroom space, underscoring the parity in their social positions and potential. As the series continues, however, Goodchild is physically separated from the street and its unruly occupants. He exists within a structured, orderly world of the polite, dutiful and successful middle class, as represented by the church, the guildhall and the ceremonial coach. Idle, on the other hand, operates outside these locales and their associated values, whether by choice or by force. His realm is the graveyard, the sea, the garret and the night cellar. Consequently, while Goodchild’s triumphal procession as Lord Mayor occurs at the heart of the City, Idle’s ignominious execution takes place in the outskirts.

Hamline University owns Plates three of twelve prints total of this series:

#536 The Industrious Prentice Performing the Duty of a Christian Plate 2

#552 The Idle Prentice Executed at Tyburn Plate 11

#551 The Industrious Prentice Lord Mayor of London Plate 12

Source: Mark Hallett and Christine Riding. Hogarth. London:Tate Publishing, 2006.

Other Individual Prints (various dates)

#524 A Chorus of Singers (1732)

A rehearsal for the oratorio Judith, written by William Huggins with music by William Defesch. Huggins was a close friend of the artist, William Hogarth, and Hogarth later painted Huggins' portrait. In its first two states this print was used as a subscription ticket for Hogarth's print A Modern Midnight Conversation. In this final state the print was sold as one of 'Four Groups of Heads', another of which was Hogarth's The Company of Undertakers (1736).

Source: Royal Academy: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/a-chorus-of-singers-1

#545 The Laughing Audience (1733)

William Hogarth's original engraving and etching entitled The Laughing Audience was first created in 1733 as a subscription ticket to his large engraving, Southwark Fair, and to his series, A Rake's Progress. The etching portrays a theatre audience. In the foreground we see the heads of three orchestra performers, all earnestly playing their instruments. Behind them is the pit where commoners are genuinely enjoying the comic drama. Only one sour faced gentleman appears not to be enjoying the performance. He is probably a critic. Above them is a private box for the upper classes. Two foppish gentlemen occupy this area and are in pursuit of love's pleasures. One makes advances to an orange girl while the other is becoming most amorous to a lady. Neither is paying any attention to the drama.

Source: Ronald Paulson. Hogarth's Graphic Works. London:Yale University Press,1965.

#559 Southwark Fair (1733-34)

Engraving by William Hogarth after his own painting Southwark Fair, reversing the image and making significant alterations to the composition. The busy scene is filled with advertisements for theatrical performances, musicians, a rope-dancer, and other entertainments. On the far left a stage collapses, and performers cling to the scaffold to avoid falling to the ground. As Einberg notes, the print was first advertised as 'a Fair' and only became identified with Southwark Fair several years after it was made, 'probably because it centres, however arbitrarily, on the old church of St George the Martyr, Southwark'. That church was torn down the year the print was made, and replaced with a new church soon after. Southwark Fair, held on September 7-9, was second only to Bartholomew Fair amongst London's fairs. The fair was abolished in 1762 owing to the increasing vice and disturbance

Source: Royal Academy: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/southwark-fair-1

#528 The Company of Undertakers (1736)

William Hogarth's original engraving and etching entitled, The Company of Undertakers is a delightful commentary upon the medical profession. Represented within a satirical coat-of-arms the engraving is bordered in black, like a mourning card. Beneath it are a pair of ominous crossbones and the motto, "Et Plurima mortis imago" -- 'And many an image of death'. The three major doctors inhabiting the upper portion of the coat-of-arms were based upon actual practitioners. In the centre of this trio is a figure dressed in a clown's suit which Hogarth refers to as "One Compleat Doctor". This figure was actually a woman named Sarah Mapp, a well known bone-setter. To her left is a feminine faced physician meant to portray Joshua Ward ('Spot Ward'), a doctor who had a birth-mark covering one side of his face. To her right, resides John Taylor, a well known oculist of the day. Taylor, it is reported, had only one eye. These physicians apparently lack the skills to heal themselves. The lower portion of the coat-of-arms contains twelve more quack doctors. Most are occupied in sniffing the heads of their canes, which, in the eighteenth century, contained disinfectant. Three doctors, however, are absorbed by the contents of a urinal. Their expressions range from sour to unintelligent.

Source: Ronald Paulson. Hogarth's Graphic Works. London:Yale University Press, 1965.

#549 March of the Guards Towards Scotland (1750)

"The March to Finchley" scene at Tottenham Court (after the painting in the Foundling Museum) features soldiers gathering to march north to defend London from the Jacobite rebels. The crowd includes, in the foreground, a man urinating painfully against a wall as he reads an advertisement for Dr. Rock's remedy for venereal disease, an innocent young piper, a drunken drummer, a young soldier with a pregnant ballad seller (her basket contains "God Save our Noble King" and a portrait of the Duke of Cumberland) and a Jacobite woman selling newspapers, a milkmaid being kissed by one soldier while another fills his hat from her pail, a muffin man, a chimney boy, and a gin-seller whose emaciated baby reaches for a drink. In the background Hogarth includes a boxing match takes place under the sign of Giles Gardiner (Adam and Eve), a wagon loaded with equipment follows the marching soldiers and, to right, prostitutes lean from the windows of a brothel at the sign of Charles II's head; beyond, the sunlight shines on Hampstead village on the hill.

Source: British Museum website: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1858-0626-369

#535 John Wilkes Esq (1763)

John Wilkes Esquire (1727-1797) was a member of Parliament and a political agitator. In 1762 he founded The North Briton, a publication that consistently attacked the government of Lord Bute, the King, and the artistic work of William Hogarth. He was twice expelled from the House of Commons but was re-elected by popular support. Such popularity made John Wilkes the lord mayor of London in 1774. William Hogarth stresses his deprived character. John Wilkes sits irreverently on his chair holding the Cap of Liberty on the Staff of Maintenance. Behind him are the issues of The North Briton where he attacks both Hogarth and the King. With twisted mouth and crossed eyes his expression is a combination of idiocy and evil. His wig is transformed into demonic horns.

Source: Ronald Paulson. Hogarth's Graphic Works. London:Yale University Press, 1965.